Publish Your Family History Without Being Overwhelmed

by Sunny McClellan Morton | Jul 3, 2013

We are often encouraged to write our family history. So we learn to interview relatives, analyze records, write compelling narratives and cite sources. Although writing is usually a solo project, sharing your writing is an integral part of the process. After all, what good is writing it if nobody will see it? Let's look at some painless ways to publish your work.

Tell Your Story as You Go

Many of us think of the classic family history book as a thick, bound volume packed with everything we've ever learned about one family line. It's a noble goal that many genealogists eventually achieve. However, it can take years to come to fruition.

Meanwhile, we can share smaller chunks of research in regular doses. Writing and publishing on an ongoing basis pushes us to analyze and document our findings while they're still fresh in our minds. The writing process helps us uncover gaps in our knowledge and make connections we may have missed previously. As we share finished writing, we connect with other interested researchers who might add to or correct what we've done. Over time, we accumulate a written body of information that can become that thick family history book. There are many different types of "smaller chunks" that we can share, including:

- A biographical sketch of a single ancestor.

- A summary of one generation's identities and lives.

- An important family event (court case, migration, job, loss or success).

- The story of an historical event, place or group of which your family was a part (like the history of a neighborhood, congregation or migration group).

- Transcribed original records: oral histories, diaries, letters, groups of tombstone inscriptions or church records, etc.

Each of these topics can be significant and interesting in their own right to certain audiences. Once we start thinking about telling our stories in installments, we can more easily identify pieces to carve out from the larger story unfolding. Then the next question becomes where we should share them.

Find a Newsletter

Newsletters published by town, county, ethnic or regional genealogical and historical societies are excellent venues for short research articles. As long as you choose an appropriate society for your topic, readers are likely to be interested and responsive. Newsletter editors generally prefer shorter pieces and may be flexible about the writing style and format. They may welcome your work even if you're not an experienced writer. Finally, the newsletter editor will lay out your work and distribute it for you.

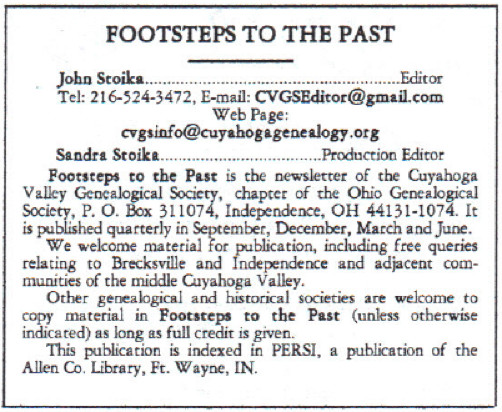

Finding an appropriate newsletter is not usually too difficult. During the research process, you've likely already connected with societies that would be interested in your topic. If not, use your web browser to keyword-search for these or use a directory like that of the Federation of Genealogical Societies' Society Hall. Once you've found a society, see if they currently publish a newsletter. Look for recent back issues online or purchase a couple from the society. Look in the front or back of the newsletter for submission guidelines, like the example shown below. Read a few articles to see whether the writing project you have in mind would be a good fit for that newsletter.

Front matter, Footsteps to the Past, Cuyahoga Valley Genealogical Society, 34:2 (December 2012), p. 10.

If so, contact the editor. Don't be shy. Newsletter editors are usually nice volunteers in perpetual need of good content. Briefly describe the type of article you have written (or want to write): the specific topic; the length (in words or single-spaced typed pages) and images you can contribute, like photos or documents. (Read about copyright issues in Thomas MacEntee's article "What You Should Know About Copyright and Genealogy." ) Many editors love images because they're interesting to readers and they take up space that the editor needs to fill.

One last consideration for choosing a newsletter: how well it's indexed and how accessible it is to other researchers. Ask the editor where people can find back issues. If you can, choose a newsletter that's indexed in PERSI (PERiodical Source Index). PERSI is an enormous index of over 2.3 million articles from over 10,000 local history and genealogy periodicals. PERSI is easily accessible to family historians at Ancestry.com.

Share Your Longer Work

If you've been working on a book-length project (even a short one), good for you! After you finish it, your next challenge is to share it widely without incurring major expenses. Here are some tips for doing just that:

Make sure your book has a title that exactly describes the content (like The Thomas and Hulda Selby Family of Camden County, Missouri). Titles like Our Wonderful Family don't tell the reader (or the person cataloging the book) what it's really about. Have a table of contents with clearly-described chapters, numbered pages and an index. Include your contact information. These items make your book easier for a librarian to catalog; a patron to identify as useful and a user to connect with you.

Donate printed copies selectively to local public libraries, such as the ones where the family lived. Also consider donating copies to major genealogy libraries like the Family History Library, the Genealogy Center of the Allen County Public Library and the New England Historic Genealogical Society. The more catalogs and shelves holding your book, the bigger the chance an interested reader will find it.

Online Options

Finally, consider web resources. Do you or a family member maintain a family blog or website? Do you have enough material, interest and know-how to start one? You can build a free site at many websites, including RootsWeb or a blog at Blogger or WordPress.

Drive traffic to your site by creating links to it from other genealogy-interest sites like Cyndi's List, Linkpendium, USGenWeb, society websites, Genealogy Blog Finder, GeneaBloggers, etc.

If you don't have a website or blog and don't want to start one, look for a website that will allow you to upload a PDF of your work. Local genealogical or historical societies may host a site that accepts user-submitted data. USGenWeb has individual pages for county-level data; look over the site or contact the webmaster to see if they will post material like yours.

If you're not quite to the writing phase, use an online family tree to attract distant cousins and collaborate on your research. Load the tree with photos, documents, stories and other sources that clearly advertise what you know. You'd be surprised at how many people will contact you because of your online tree. If you haven't already done so, start building your online family tree here at Archives.com (from the home page, click on "My Tree").

Conclusion

As you can see, you have a lot of choices for publishing and distributing your written family history, whether you've got one page worth of material or one hundred. There's no reason to keep putting your writing project on hold, thinking one day you'll write your tome. Start writing and sharing now and your research efforts will be preserved and magnified for present and future generations to enjoy.

Resources: More Expert Series Articles About Writing Your Family History

- Lisa Alzo, "Break That Writer's Block: Ten Tips to Tap Into Your Creative Muse"

- Lisa Alzo, "Six More Ways to Find Your Family History"

- Harold Henderson, "Why We Don't Write, and How We Can"

- Lou Liberty, "Writing the Story of Stories"

- Betty Malesky, "Breathe Life Into Your Ancestor's Story"

Find Records Now for Free

Start your free trial today to learn more about your ancestors using our powerful and intuitive search. Cancel any time, no strings attached.